|

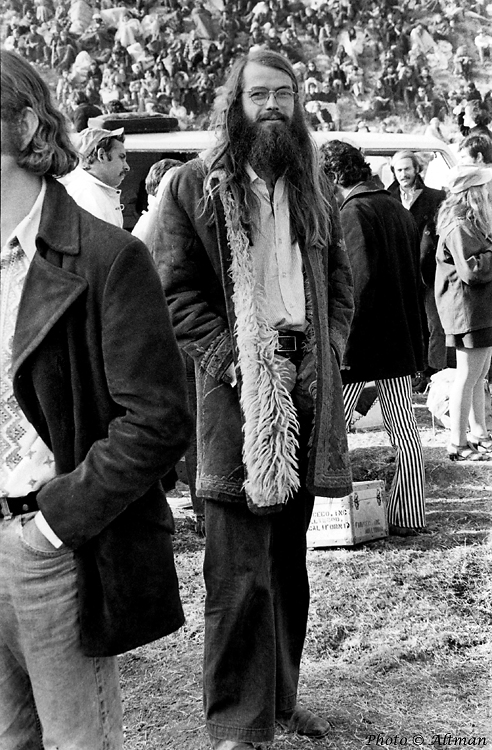

| Photo- Robert Altman - ©

2005 |

|

| Photo- Robert Altman - ©

2005 |

Chet Helms

Producer- The Family Dog - 1969

|

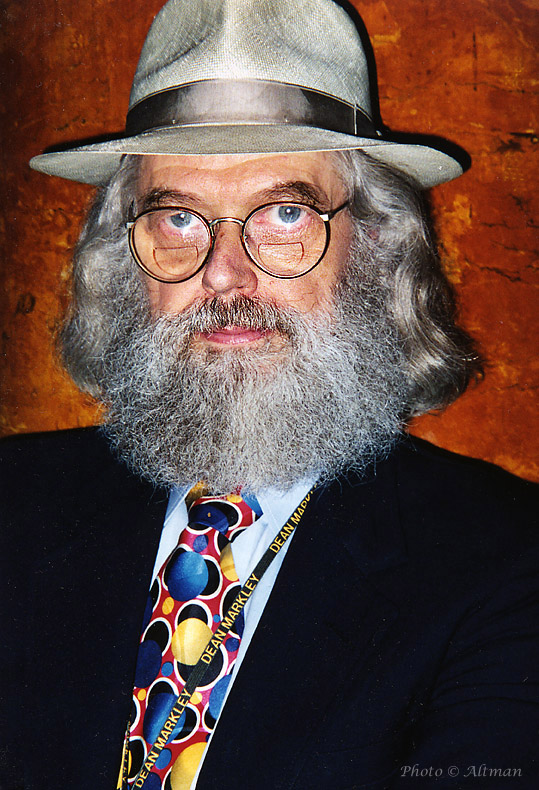

| Photo- Robert Altman - ©

2011 |

Chet Helms -- Legendary S.F. Rock Music Producer

Aidin Vaziri and Jim Herron Zamora, Chronicle Staff Writers

Sunday, June 26, 2005Chet Helms, a towering figure in the 1960s Bay Area music scene who brought Janis Joplin to San Francisco and ran the Avalon Ballroom during the Summer of Love, died early Saturday after suffering a stroke last week. He was 62. "Chet Helms was like one of the founding fathers of music scene here," said Mickey Hart, drummer for the Grateful Dead and many other bands. "He was really the heart and soul of the music scene here in San Francisco. He was more than just a promoter. The Avalon really captured the spirit and the vibe of the era."

Mr. Helms, who stayed true to his hippie ideals through four decades, died at 12:25 a.m. at San Francisco's California Pacific Medical Center surrounded by a dozen of his closest friends and relatives, said his wife, Judy Davis. "It was a beautiful death," Davis said. "It was a goodbye party. We all sang to him and told stories. We had a chance to really show our love and say goodbye. He died as he lived -- surrounded by love."

Chester Leo Helms was born Aug. 2, 1942, in Santa Maria (Santa Barbara County), the oldest of three sons of Chester and Novella Helms. When Mr. Helms was 9, his father, who worked in a sugar beet mill, died. His mother took the boys to Texas, where they were raised by a fundamentalist preacher grandfather.

He migrated to San Francisco after dropping out of the University of Texas in 1961 and soon found his way to a boarding house at 1090 Page St. Falling in love with rock music after attending a Rolling Stones concert at Civic Auditorium, he began hosting jam sessions in the rosewood-paneled basement ballroom of the Haight-Ashbury house. Big Brother and the Holding Company emerged from those parties, and Mr. Helms, the band's manager, brought old college friend Joplin up from Texas to be their singer.

"Without Chet, there would be no Grateful Dead; no Big Brother and the Holding Company; no Jefferson Airplane, no Country Joe & the Fish; no Quicksilver Messenger Service, and the list goes on," said Barry Melton, the lead guitarist for Country Joe & the Fish.

"He wasn't just a promoter; he was a supporter of music and art. He supported people emotionally, psychologically and psychically. He really made the scene what it was."

Mr. Helms and the late Bill Graham teamed up to produce three shows at the Fillmore Auditorium in 1966 before Graham went off on his own to build the Fillmore into one of the most important venues in rock history. Mr. Helms continued producing concerts under the name Family Dog at the Avalon Ballroom, an old dance academy at Sutter and Van Ness. But Mr. Helms lacked both Graham's capitalist drive and his killer instincts. Where Graham built a rock 'n' roll empire before he died in a helicopter crash in 1991, Mr. Helms was forever a hippie zealot with a missionary's dedication. "He was like Bill Graham, but he was the soft side; he was sweet as sugar," Hart said. "His business sense wasn't as keen as Bill's but he really believed in the music."

Melton said, "He was the antithesis of Bill Graham. Chet didn't really care about money. The music always came first." But Davis stressed that while there was a rivalry between Mr. Helms and Graham, it was cordial. "They always got along. It was a friendly rivalry."

Although the Avalon was known as a far more authentic alternative to Graham's more commercial Fillmore Auditorium operation -- Joplin once famously earned Graham's ire by saying the Fillmore was "a place where sailors go to get laid" -- Mr. Helms' business ultimately foundered. By November 1968, after the city pulled his sound permits on the Avalon, he was looking elsewhere for a place to stage his shows. Mr. Helms moved his operation to an old slot-car raceway near Ocean Beach, but Family Dog on the Great Highway ran out of money in less than a year, and Mr. Helms left the concert business in 1970.

"Chet was a hippie," Hart said. "We were all hippies. He hated to charge for the music." Mr. Helms ventured back into the concert business in 1979 with Tribal Stomp II, an ambitious festival at the Monterey County Fairgrounds, but it was a financial disaster. In 1995, he resurfaced again, lending the Family Dog name to a group producing concerts at the Maritime Hall. That venture lasted only seven months.

"He never approached anything in a businesslike way," said Lee Houskeeper, his publicist and longtime friend. "He was always broke."

In October 1997, he attempted to pull together an ambitious two-day event featuring young and old bands by reconvening the long-dormant Council for the Summer of Love -- a hippie-era Haight-Ashbury community group -- for a 30th anniversary celebration. He even tapped then-Mayor Willie Brown for help during a fund-raiser for the concert. "Now's the time to put in that call to Carlos, Mr. Mayor,'' Mr. Helms said, referring to one of the most enduringly successful Bay Area musicians, Carlos Santana.

In the end, however, the event evolved into a chaotically organized free concert at Beach Chalet Meadows in Golden Gate Park with nostalgic headliners like Jefferson Starship, Sons of Champlin and Country Joe McDonald. Still, more than 10,000 people turned up for the 11-hour event.

A year later, the city demanded that organizers for the event pay $29,407 for police overtime costs, to which Mr. Helms replied: "We will make every effort to pay. But I don't have $29,000. I don't think among us we have $29,000. You can have my jacket."

Since 1980, Mr. Helms ran a small art gallery on Bush Street, Atelier Dore, bought with proceeds from the auction of a valuable painting he lucked into when he was low on finances. That score was about all he had to show for his years as one of the key players in the flourishing '60s San Francisco rock scene.

He also began experimenting with visual arts himself, taking thousands of digital photographs. "He really turned toward digital photography in recent years," Davis said "It gave him a lot of pleasure." Before the stroke, Mr. Helms had been grappling with hepatitis C, a contagious viral disease that usually leads to serious, permanent liver damage. Houskeeper said that the various prescription medications Mr. Helms took to treat the illness seriously affected his strength.

"He seemed to be getting better for awhile," Davis said. "We were very hopeful. But then things got worse pretty fast." Last Tuesday, Mr. Helms suffered a mild stroke, and on Friday afternoon a CAT scan revealed a clot on his brain. "We had dozens of visitors and even more phone calls,'' Davis said.

In addition to Davis of San Francisco, Mr. Helms is survived by his step-daughter, Sarah Davis of San Francisco; brothers John Helms of San Francisco and Jim Helms of Hawaii; and three grandchildren. Services are pending.

Chronicle Senior Pop Music Critic Joel Selvin contributed to this report.

http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2005/06/26/HELMS.TMP